From Creditanstalt to UBS-Credit Suisse: The Dangers of Merging Troubled Banks

“You will merge with UBS and announce Sunday evening before Asia opens. This is not optional.”

This message from the Swiss “trinity” of the Swiss National Bank (SNB), regulator FINMA, and the minister of finance was delivered to Credit Suisse management before the failure of Credit Suisse in March 2023 became public.

It was later reported that this proposed forced merger was opposed by UBS and Credit Suisse management.

One of the most contentious aspects of the deal is that UBS shareholders will not be required to approve it. This is due to the fact that the Swiss government modified the law shortly before the takeover to eliminate any potential ambiguity.

The desperation of Swiss authorities to contain potential fallout and stop panic spreading in markets was difficult to ignore. Eventually, the deal to merge both banks went through at all costs in the name of protecting Swiss national banking interests.

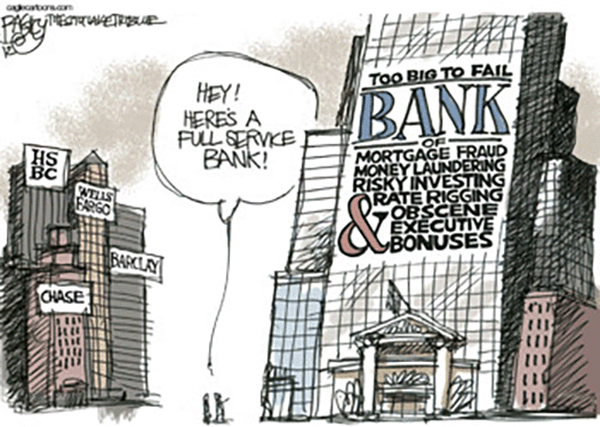

At its core, the frantic merger of UBS and Credit Suisse was another chapter in the all-too-familiar topic of ‘too big to fail’ banks. Credit Suisse as Switzerland’s second-largest bank was itself too big to fail. It was merged with Switzerland’s biggest bank, UBS – another too big to fail bank that was rescued by the government and the SNB in the 2008 financial crisis.

As a result of the merger, the newly formed UBS Swiss banking behemoth will become the second-largest mutual funds and ETFs provider in Europe after US asset manager Blackrock.

The size of this single super big bank has sparked sarcasm that the new UBS is now ‘the world’s safest bank’ because Switzerland has made it too big to fail.

But is it?

Too Big to Fail is Not New

The phrase "too big to fail" has become a common refrain in discussions of the banking industry in recent years, as concerns about the risk posed by large, systemically important financial institutions have grown.

But the idea that some banks are simply too large and interconnected to be allowed to fail is not a new one.

In the early 20th century, there were universal banks - large, diversified financial institutions that engaged in a wide range of activities, from commercial and investment banking to insurance and asset management.

Like today's "too big to fail" banks, universal banks of the 1920s were seen as crucial to the functioning of the financial system and the broader economy, but their size and complexity also made them risky and difficult to regulate.

Creditanstalt: Austria’s Super Bank in the 1930s

Creditanstalt was a major Austrian bank founded by the famous Rothschild banking family in 1855 that grew to become Austria’s largest bank and one of the largest and most influential financial institutions in Central Europe by the early 20th century.

It was one of four universal Austrian banks - the Verkehrsbank, the Unionbank, the Boden-Credit-Anstalt. These banks engaged in both commercial and investment banking activities, and also had ownership stakes in industrial enterprises, essentially making them both lenders and owners – an industrial network known as Konzern.

However, the weak performance of these Konzerns in the 1920s reduced the banks’ profitability as a result of loans provided to Konzerns.

The Austrian banks’ situation was also under stress following the hyperinflation of 1923-1924, as they were unable to sufficiently replenish their capital endowments, resulting in an increasing reliance on debt financing for their ventures.

In 1926, the Verkehrsbank and the Unionbank sank into distress. The Bodencreditanstalt, then Austria’s second-largest bank, took over both bankrupt banks. The acquisition soon put the Bodencreditanstalt in jeopardy given its mismanagement of the bad loans inherited from the Verkehrsbank and the Unionbank.

Austria’s second-largest bank was on the brink of collapse.

Fearing spreading market panic and a loss of confidence, the Austrian government led by Johannes Schober intervened forcefully and arranged for the Creditanstalt, Austria’s biggest bank, to acquire the Bodencreditanstalt and the bank's assets.

The Creditanstalt Crisis Begins

This forced bank merger created a single Austrian super bank in the Creditanstalt, concentrating the accumulated losses of the Austrian banking industry. The bank also accounted for 27% of the total assets of the Austrian banking sector, which was equivalent to 16% of the country's GDP.

About 69 percent of Austrian limited liability companies conducted their operations with Credit-Anstalt, and approximately 14 percent of them were significantly indebted to the bank.

Unfortunately, the Creditanstalt was itself burdened and dragged down by this acquisition.

On 8 May 1931, the Credit-Anstalt informed the Austrian government and Austrian National Bank of its financial difficulties.

The Austrian Government Tried to Save the Credit-Anstalt

The Credit-Anstalt was deemed too big to fail, given that it had business ventures in eleven banks and forty industrial companies within the territories of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire even after the empire's collapse after World War I. It had 130 significant foreign creditors in banks, primarily in the UK and the US.

Above all else, Credit-Anstalt had a remarkable global standing, particularly due to the fact that its president, Louis Rothschild, was a member of the Rothschild family. As a result, the bank had more favorable terms in worldwide financial hubs than any other German banks.

Given Credit-Anstalt's significance to the financial system, the Austrian government put together a rescue plan within three days for the losses to be absorbed by the Austrian state, the Austrian National Bank, the Rothschilds, and the shareholders.

The Creditanstalt made an announcement on May 11, 1931, stating that it had lost over 50% of its capital, which was the threshold under Austrian law for a bank to be deemed as failed.

The Creditanstalt’s failure came as a shock as it was considered impregnable and was one of the most important financial institutions of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Panic ensued and confidence plummeted resulting in bank runs on Austrian banks.

Financial Contagion Spreads and the Great Depression Begins

The crisis set off a chain reaction causing distrust in banks to spread from Viennese banks to banks in central and eastern Europe, and bank runs and bank failures became increasingly common.

Austrian citizens were concerned that the 1924 inflation crisis would reoccur, leading to the collapse of both the Austrian currency and banks. To mitigate the potential effects of devaluation, people started to exchange their schillings for foreign currency.

The Credit-Anstalt crisis also initiated and deepened the Great Depression in Europe and severely impacted European economies. Contagion from the 1931 Austrian banking crisis spread to Great Britain, causing it to go off the Gold Standard, depreciating the sterling pound against the U.S. dollar. Twenty-five countries followed suit and before long, the Depression was global.

Panic at the Savings Bank of Berlin in 1931

With the Same Playbook, Is History Repeating?

The merger of Switzerland’s two largest banks has eerie similarities with the Creditanstalt collapse.

Firstly, the merging of troubled banks was already practiced a century ago, with bad results.

Secondly, the government forcing a rescue does not necessarily resolve or contain financial contagion.

Thirdly, even in the era of the almighty government money-printing machine and central bank forward guidance, banks have no real defense against age-old loss-of-confidence bank runs.

In the case of Credit Suisse, when investors got wind that the Saudi National Bank (SNB), the bank's largest shareholder, declined to buy more of the bank's shares, it triggered a seismic loss of confidence and a bank run.

The playbook to deal with failing banks seems unchanged despite being a century apart.

Moreover, bank runs in the digital age as witnessed by Silicon Valley Bank’s failure demonstrate how stunningly swift funds can be transferred digitally from bank accounts.

It reiterates the fact that the market is always bigger and quicker than the government and what it can do with monetary policy. The speed of the market is also bad news for depositors as it is often too late to withdraw deposits in the event of a bank run before regulators step in to halt withdrawals.

It begs the question of what Plan B one has to mitigate a banking crisis.

What is Your Plan B?

Precious metals like gold and silver held securely are excellent Plan B assets. By themselves, physical gold and silver have no counterparty risks to the banking system and allow wealth to be held outside the financial system.

Precious metal wealth is even more ironclad when you store them securely in a safe jurisdiction like Singapore with a specialized wealth protector like Silver Bullion. Our S.T.A.R. Storage program ensures that you are an owner of your bullion, not a creditor. We also have one of the best insurance policies for vaulting precious metals in the industry.

In addition, our exclusive Singapore jurisdiction minimizes customers’ foreign jurisdiction governmental nationalization exposure.

In today's world, where the banking system is still vulnerable to economic crises and bank failures, it is essential to consider diversifying one's wealth management strategy.

Doing so can protect your wealth from potential risks and preserve it for future generations.