History of Silver As Money: From Ancient to Modern Times

As a wealth protection company dealing in precious metals for over a decade, it is common for our clients to ask about silver’s history as money from time to time.

While some may recall the U.S. demonetization of silver in the 1960s, many are unaware that silver has been the main monetary metal since ancient times. In fact, silver was used as money more often than gold throughout mankind’s history. Our predecessors chose silver as the medium of exchange not by government decree but because it fulfilled all the characteristics of money, like gold.

Moreover, many currency names today trace back to their silver roots. While money today is entirely fiat currency, silver’s historical use for millennia as money is an important reminder that silver, like gold, continues to be a safe-haven asset that protects against currency debasement and monetary inflation.

Silver Money in the Ancient World

Ancient Silver Shekel

Silver was already a means of payment as early as 3000 BC. The shekel was not a currency but one of the oldest known units of weight. It originated in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) and was used by the Sumerians. The Sumerian word for “shekel” is “giĝ,” meaning “axe.”

During the Akkadian Empire from 2334 BC, the Akkadian word šiqal (or sheqel), meaning "to weigh" or "to measure,” is believed to be how the word “shekel” is derived. The early Mesopotamian shekel, weighing approximately 8.33 grams of silver, was the principal unit for measuring silver.

The fall of the Akkadian Empire resulted in the nation’s split into Assyria and Babylonia, with the shekel continuing to be adopted as a standard weight and value for their own systems of trade and exchange.

Ancient silver pieces discovered from archaeology.

Biblical Silver Shekel

The shekel’s use in ancient Israelite society, as detailed in the Hebrew Bible, is arguably its most famous use in history. The first mention of the shekel is in Genesis 23:16 when the patriarch Abraham bought a piece of land for 400 shekels of silver.

Prior to the advent of coin minting, these silver pieces were crudely cut from broken pieces of silver ingots, jewelry, tableware, and scrap silver. Regardless, they had a recognized value in society and facilitated regional trade. It was not until after 400 BC that coins were used in Israel.

Silver pieces from Tel Megiddo. (credit: Clara Amit/IAA)

Greek Staters

The Greek historian Herodotus recorded that the first coins, called stater, were struck in the Kingdom of Lydia around the seventh century BC. Known as the Lydian Lion stater, the coins were made from a silver and gold alloy known as electrum.

The advent of Lydian coins began when electrum was stamped with seals or signet rings to increase confidence in the precious metal’s weight and purity. In ancient times, stamping on something like a clay tablet or electrum signified the full power and prestige of the seal's owner.

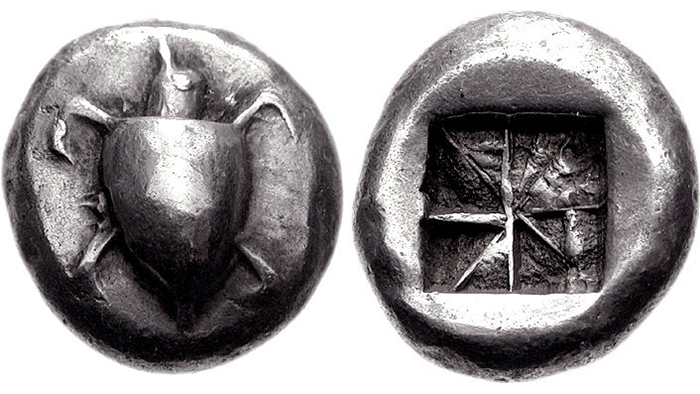

Around 560 BC, Lydia’s trading partner Aegina minted its first silver stater coins, including a coin featuring a sea turtle in high relief.

Depending on the issuing region, Greek staters were minted with different weight standards. For example, Athens produced the 17.4 g tetradrachm stater using the Attic weight standard, Aegina’s weight standard produced 12.4 g staters, and the Corinthian standard minted 8.6 g staters.

Ancient Greek silver turtle stater coin

Roman Denarius

The Roman silver denarius was one of the most famous coins in the world, and it was mentioned several times in Christ’s teachings in the Bible.

Before the minting of the denarius, the traditional Roman currency had been raw bronze (aes rude in Latin) and heavy bronze coinage (aes grave). As the value of each bronze coin was low, using these coins in bulk became cumbersome in commerce and they were eventually replaced by silver coinage.

As Greek silver coins gradually circulated into the Western Roman Empire, Rome began to mint their version of the silver coin.

Called the ‘denarius,’ meaning “containing ten (bronze) aes,” the Roman silver coin was stamped with an ‘X’ to signify this value. It was minted shortly before 211 BC had roughly 4.5 grams of silver.

The Roman silver denarius was to become the major silver coin of the Western Roman Empire for the next 500 years, and it was used to pay the mercenaries in the Roman armies.

However, beginning from 64 AD, the silver content in the denarius, which was between 95% to 98%, was reduced to 93.5% by Emperor Nero to cover the extravagant spending of the empire. The coinage was debased to 83.5%, then 78.5%, and 50% over time. Eventually, the denarius became a silver-plated copper coin.

Given the extent of the Roman Empire, the denarius was one of the most widely used coins of the ancient world. Still, its prominence gradually diminished due to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD, even though it continued to be used in the medieval period and was later replaced by other silver coinage.

Roman denarius silver coins

Silver Money in the Medieval Period (500 to 1500 AD)

Byzantine Silver Coins

The Eastern Roman Empire survived the Western Roman Empire, otherwise known as the Byzantine Empire, with its capital at Constantinople (modern Istanbul). This empire continued for nearly 1,000 years after the fall of the West.

Silver was not the dominant metal in Byzantine coinage. Instead, the solidus gold coin (typically weighed around 4.4 to 4.5 grams), introduced by Emperor Constantine I between 309 and 312 AD, was the cornerstone of Byzantine economies.

Silver miliarense and siliqua also circulated during this time, serving as silver alternatives to gold solidus, which was the main currency unit for larger transactions. The silver miliarense weighed about 4.5 grams and was 1⁄18 of a solidus, while the siliqua weighed half of the miliarense and had a 1⁄24 ratio to the gold coin.

During the seventh century, Emperor Heraclius requisitioned silver from the churches of Constantinople to introduce the hexagram, a large silver coin weighing between 6.70 and 6.85 grams, valued at 1⁄12 to the solidus. The hexagram circulated for about 70 years, after which silver coinage seemingly disappeared from the Byzantine economy.

Silver coinage returned to the Byzantine Empire in the eighth century, when Emperor Leo III introduced the miliaresion, a lightweight silver coin weighing about 2.25 grams, as part of a broader series of monetary reforms that sought to stabilize the Byzantine economy.

The miliaresion served as a middle-range coin between the gold solidus (used for larger transactions) and the smaller bronze coins used for everyday purchases. Its introduction was particularly significant during a period of great economic strain and after a period of debased coinage.

Byzantine miliaresion silver coin

Silver Penny

The penny was a silver coin introduced by the Anglo-Saxon king Offa of Mercia (757–796 CE) around the 8th century. The first pennies are thought to have been indirectly derived from the Roman denarius coin.

King Offa’s silver penny weighed approximately 1.3 to 1.5 grams and was part of a reform to standardize coinage in his kingdom. It was made of fine silver and often featured a simple design with a cross and the king's name or title.

The Viking invasions in the 9th and 10th centuries did not eliminate the silver penny but led to variations in coinage, such as coins minted in the Danelaw (Viking-controlled areas of England) with different designs.

After the Norman Conquest in 1066, silver pennies continued to be minted under William the Conqueror and his successors.

By the 12th century, England began to experience debasement of the penny as monarchs started to reduce the amount of silver in coins to meet the costs of war and administration.

The last official silver pennies in England were minted during the 17th century, but as the centuries progressed, the penny became predominantly copper and then bronze by the early 19th century.

Silver Dirham

The silver dirham has its origins in the Sassanian Empire and was adopted and adapted by the early Islamic Caliphates following the Arab conquests of the 7th century.

Caliph Abd al-Malik initiated a major reform of the Islamic coinage system in 696 AD, effectively replacing the earlier Byzantine and Sassanian coins with new, standardized Islamic coins. This was part of his broader effort to consolidate Islamic identity and assert political control across the empire.

The dirham was introduced as the primary silver coin. It was modeled on the Sassanian drachm, but it had significant changes to reflect the Islamic faith and the political identity of the Islamic state.

The Umayyad dirham was made of high-purity silver, with an initial weight of around 2.7 to 3 grams—similar to the Sassanian drachm.

The Abbasid Caliphate inherited the dirham and continued to mint it in large quantities. The Abbasid dirham was very similar to the Umayyad dirham, but with variations in the inscriptions and designs, reflecting the shifting religious and political context of the Abbasid era.

The dirham continued to be minted by subsequent Islamic dynasties, including the Seljuks, Mamluks, and Ottomans, although the coinage evolved with varying designs and silver content over time.

Silver Florin

The silver florin, weighing 3.53 grams, was first introduced in Florence, Italy, in 1252. Up until this time, Western Europe's coinage had been predominantly silver for some 500 years.

The silver coin was initially minted as part of the city's efforts to establish a stable and widely accepted currency for trade and commerce, especially as Florence became a major financial and commercial hub during the Italian Renaissance.

By the late 15th century, the silver florin's use began to decline. Florence, while still economically prosperous, faced increasing competition from other powerful Italian city-states and external forces such as France and Spain.

Chinese Silver Sycee

In China, as early as the Tang Dynasty, silver was used in trade and as a store of value, especially for large transactions, although it was not considered an official currency.

Under the Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty founded in 1271, silver became a critical component of the monetary system. Emperor Kublai Khan introduced silver-backed paper money and the government promoted the use of silver sycees (or yuanbao) for trade and taxation.

However, as with all experiments with paper currency, it was often over-issued, leading to little trust in it. It often traded below face value and, over time, became worthless as the value declined.

The Ming Dynasty standardized on silver because people lacked confidence in paper money. Measured in taels, silver sycees circulated alongside silver strips, foreign silver coins, and fragmentary silver.

Silver Money During the Early Modern Period (1500 to 1800 AD)

Spanish Real and the Spanish Dollar

The Spanish real was introduced in the mid-14th century under Pedro the Cruel, King of Castile and León. However, it was not until 1497, when Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile initiated monetary reforms, that the real was established as a base currency in the region.

These reforms prepared the Spanish mints for the subsequent massive inflow of bullion from the discovery of precious metal deposits in the Spanish Empire’s territories in the Americas, allowing it to increase the production of the silver real.

Silver reales were minted in 1⁄14, 1⁄2, 1, 2, 4 and 8-real denominations. The 8-real was known as the “Reales de ocho” or pieces of eight, weighing about 27 grams of fine silver. Its consistent weight, high silver purity (92.5%), and milled edge, which discouraged clipping, made it a standard for trade within Spain and internationally.

The eight reales began circulation in Europe and eventually spread to the Americas, Southeast Asia, and China. As its international use expanded, especially among English-speaking merchants, the name "Spanish dollar" became commonly accepted. The word "dollar" is an Anglicization of "thaler," the name of the Habsburg silver coin minted in German-speaking areas.

The Spanish dollar is frequently described as the world’s first universal currency, given its popularity in international trade from the late 15th century to the 19th century.

Spanish dollar real de ocho

Bohemia Thaler

The increased supply of silver and the growing demand for money during the early Renaissance led to the creation of new large silver coins. At that time, Europe was a continent of city-states with local rulers vying for power and no standard monetary unit among them. One of the rulers' most effective ways to assert control was to mint their currency, which a local lord, Count Hieronymus Schlick, did.

When rich silver deposits were discovered in the Joachimsthal in Bohemia in 1516, Schlick exploited the mines and struck large silver coins in 1520 called the Joachimsthaler Gulden, meaning "Joachim’s Valley" and "Gulden," a term used for money. This coin would be the first of many referred to as thalers.

A silver thaler weighed 29.2 grams and had a purity of at least .889 silver. It gave Europe a standard monetary unit for trade within the city-states, provinces, and kingdoms of the Holy Roman Empire.

Many countries were to produce versions of this coin and its name: daler, daalder, tallero. Dollar was the version of the name adopted in England and was often applied to the large silver coins of Spain and Spanish America.

Silver Money in the Modern Period (1800 AD to Present)

Mexican Silver Dollar

When Spain colonized Mexico in 1521, it introduced the Spanish Dollar, a silver coin widely used throughout the Spanish Empire. Mexico's abundant silver mines, especially in Zacatecas and Guanajuato, made the colony one of the world's largest silver producers.

In 1535, the Casa de Moneda de México (Mexican Mint) was established, the first mint in the Americas and it produced coins such as the Spanish Dollar.

After gaining independence in 1821, the Mexican Mint produced Mexican Silver Dollars or Silver Pesos under the new Republic. These coins retained the Spanish Dollar's weight and fineness, ensuring worldwide acceptance.

Mexican Silver Pesos dominated global trade in the 19th century, especially in Asia, where they were widely accepted and often countermarked by local merchants to ensure their authenticity.

As countries moved to the gold standard, the dominance of silver currencies waned towards the late 19th century.

By the mid-20th century, Mexico ceased using silver in its circulating pesos due to rising silver prices.

American Silver Dollar

The history of the first American silver dollar coins dates back to the late 18th century, shortly after the United States was founded in 1776. These coins were inspired by earlier Spanish silver dollars (real de ocho) and reflected the nation's aspirations for a stable and respected monetary system.

Before independence, the American colonies relied on foreign coins, particularly Spanish dollars, which were widely circulated and trusted due to their consistent silver content. After independence, the U.S. sought to establish its own currency to unify the economy and assert sovereignty.

The Coinage Act of 1792, passed by Congress, established the U.S. Mint and laid the groundwork for a national monetary system. It defined the dollar as the standard currency unit inspired by the Spanish dollar in terms of size and silver content.

A silver dollar would weigh 416 grains or 26.96 grams, similar to German thalers. The Coinage Act also set the silver-to-gold ratio to 15:1, meaning one troy ounce of gold would buy 15 ounces of silver.

In 1794, the first U.S. silver dollar, the Flowing Hair Dollar, was minted. A year later, the Flowing Hair design was replaced by the Draped Bust design which was minted until 1804. These early U.S. silver dollar coins would set the stage for future silver dollar designs, including the Morgan Dollar and Peace Dollar.

Flowing Hair Dollar

Chinese Silver Coins

By the mid-19th century, China’s international trade with Western powers had grown significantly and was mainly conducted in foreign silver dollars such as the Mexican Peso and the American Dollar.

In response to increasing foreign trade and the inefficiency of using silver sycees (ingots) and different local and foreign silver coins with varying weights, the Qing government decided to mint its own standardized silver currency. These coins became known as "Dragon Dollars" due to their iconic dragon motifs.

The first Dragon Dollars were minted at the Guangdong Mint in 1889, marking the beginning of China's transition to a modern coinage system. These weight of each silver coin was set at 7 mace and 2 candareens (26.86 grams) and had a 90% silver purity.

With the transition of the Qing dynastic government to the Chinese Republic, China continued producing silver coins of similar specifications to the Dragon Dollar but bearing the image of its politicians. Examples include the Yuan Shikai Dollar struck in 1914, which weighed about 27 grams and had an 89% silver purity, and Sun Yat-sen silver coins that were struck following the Nationalist government’s coming to power in 1928.

When Franklin Roosevelt was elected President of the United States in 1933, his administration introduced a series of federal acts to increase the silver price, including the 1934 Silver Purchase Act. This decision was to fulfill promises made to Congress' silver bloc, representing silver-producing states, for election support.

The intent of introducing the Act was to force the Treasury to buy silver until the global silver price reached $1.29 per ounce. Should this goal fail, the Treasury was to buy silver until U.S. silver reserves were a fourth of the monetary value of all U.S. bullion.

The enactment of these U.S. government policies quickly increased silver prices within a few years, impacting China, which was on a Silver Standard.

Higher silver prices encouraged investors to withdraw silver from China and sell it in London. Silver drained out of China, seriously decreasing Chinese silver reserves and potentially collapsing the country's banking and monetary system.

These domestic economic challenges led China to abandon the silver standard in 1935 and nationalize the country’s silver reserves. Dragon Dollars and other Chinese silver coins were withdrawn from circulation and replaced by fiat currency.

U.S. Demonetization of Silver

While the enactment of the 1934 Silver Purchase Act was meant to support the U.S. domestic silver industry, it inadvertently impacted the American silver industry in the long term, leading to reduced monetary demand for silver abroad.

Countries like China and Mexico abandoned the Silver Standard post-enactment of the 1934 Silver Purchase Act due to the economic pressures brought on by silver price volatility.

The Act had required the U.S. Treasury to buy huge amounts of silver from the market to maintain an artificially set price of $1.29 per ounce, the monetary value of silver in U.S. coinage. Silver price differential in the Chinese and Mexican markets increased silver exports and drained silver reserves needed to support their silver-dependent monetary systems, destabilizing their local economies.

Conversely, the artificially high silver price led to a surge in silver exports to the U.S., ballooning its silver reserves significantly.

After the Second World War, industrial demand for silver increased, while its use as a monetary declined. Federal Reserve Notes were backed by gold, not silver. The government’s stockpiling of silver was questioned over time due to the increasing costs of silver storage in federal depositories such as the West Point Bullion Depository, the no longer need to satisfy silver-mining state politicians with silver buying, and silver’s diminishing monetary role.

Industrial demand for silver accelerated in the 1960s, causing the price to rise above the official price of $1.29 per ounce. The government began to sell off its silver stocks.

In 1963, the Silver Purchase Act of 1934 was repealed by Congress, ending the Treasury’s silver purchase obligation. Silver certificates were gradually retired with the issuance of $1 and $2 Federal Reserve Notes.

The Coinage Act of 1965 removed silver from dimes and quarters and reduced its content to half dollars, significantly reducing silver’s need in currency.

Electronics demand from the 1970s to 1990s eventually depleted the government's silver stockpiles.

Why Invest in Silver

The history of silver as money is indeed long, spanning ancient to modern times, and is aa testament of it being an excellent and trusted store of value, like gold. While its role as currency has diminished in today’s fiat-dominated world, silver remains a sought-after asset.

Unlike paper currency, silver has intrinsic value due to its physical properties and historical use as money. Its dual role as an industrial metal and a precious metal ensures demand beyond investment, supporting its value throughout millennia.

Throughout history, silver has been a “safe haven” during times of crisis. Its portability and global recognition make it an asset of choice, especially during economic turmoil. Whether during hyperinflation, war, or currency devaluation, silver has consistently retained value when other forms of wealth faltered.

Silver coins have been trusted forms of currency for millennia, from the shekels of ancient Mesopotamia to the Spanish pieces of eight and U.S. silver dollars.

Additionally, silver’s unique properties make it indispensable in industries like electronics, renewable energy, and medicine. As these sectors grow, demand for silver is expected to rise. Simultaneously, diminishing silver mining yields add an element of scarcity, potentially driving up prices over time.

Finally, the current gold-silver ratio is historically high, indicating that silver is undervalued compared to gold.

Whether as a crisis hedge, an investment, or a connection to its rich monetary history, silver remains a compelling choice for individuals looking to diversify their holdings and safeguard wealth.

How to Invest in Silver

While there are many ways to invest in silver, the safest way is undoubtedly to buy silver bullion bars and coins – tangible assets that you can store safely outside the financial system.

Physical silver has no counterparty risk, meaning that, unlike investments such as stocks or fiat currency, it is not dependent on a third party to fulfill promises. A crisis in the financial system will not majorly harm your bullion bars and coins that are safely stored.

Visit Silver Bullion’s retail store at Millenia Walk in Singapore to purchase silver bars and coins. Our knowledgeable staff can assist you with your purchase or provide any information about precious metals you may need.