Not Worth a Continental

“Do you think, gentlemen, that I will consent to load my constituents with taxes when we can send to our printer and get a wagon load of money, one quire of which will pay for the whole?”

This statement attributed to a delegate of the Second Continental Congress betrayed the allure of printing money for politicians.

The choice was simple: risk becoming unpopular by levying taxes or fire up the printing presses behind the scene and get a wagon load of money to solve fiscal issues with one’s popularity intact.

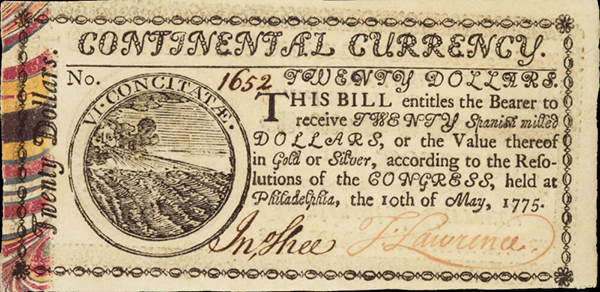

The Second Continental Congress convened in May 1775 and was preparing for war, a month after the first shots between the Continental and the British army had been fired at Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts. The American Revolutionary War had begun.

With little gold and silver in hand and facing a war against Great Britain, the greatest colonial power in the world, the Continental Congress chose printing money over taxation as the main funding source. With the total money supply of the United States at the start of the war consisting of about 12 million dollars in gold and silver coins (specie), the Continental Congress began issuing $2 million Continental paper money by mid-1775. Just four days later, another $1 million Continentals were authorized. In a span of a few months, the money supply had increased by 25 percent.

However, no one foresaw the bottom of the money printing slippery slope as Congress ended 1775 issuing $6 million, $19 million in 1776, $13 million in 1777, $64 million in 1778, and $125 million in 1779. Continental paper dollars issued over five years ballooned to over $225 million.

With so much paper money in circulation, the value of Continental paper depreciated rapidly and prices skyrocketed. People hoarded gold and silver specie money and spent the ‘bad’ Continental paper money first – a case of Gresham’s Law.

It is no wonder then that George Washington wrote to the president of the Continental Congress in 1779, “In the last place, though first in importance, I shall ask, is there any thing doing, or that can be done, to restore the credit of our currency? The depreciation of it is got to so alarming a point that a wagon-load of money will scarcely purchase a wagon-load of provisions.”

The depreciation of the paper in terms of specie was indeed alarming; Continentals were worth $3 to $1 in specie by the fall of 1777, and the ratio had plummeted to 42 to 1 by December 1779. They were practically worthless by the spring of 1781 with a market exchange rate of $168 paper dollars to $1 in specie. This was how the expression “not worth a Continental,” came into the lexicon during the Revolutionary War.

The government did its best to prop up the currency but to no avail. With their powers, several laws were enacted requiring people to accept paper money and to fix the prices of goods. The attempt at price control only resulted in the effect of eliminating goods from the market. Even pro-independence farmers preferred to sell their harvests to the British because they were paid gold and silver.

The laws demanding legal tender and price control ultimately failed. The more the government tried to force the acceptance of bad money, the more the public shunned paper money. The problem was a lack of confidence in the creditworthiness of the issuer at a time of a protracted war.

Supplies and some measure of trust returned only when Congress abandoned its legal tender laws and began to pay for goods with mustered gold and silver from the states or borrowed from allies like France. Regardless, so deep was the public distrust of paper money that it wasn’t until the Civil War that paper money was issued again in any substantial quantity.

It was this disastrous experience with Continentals that motivated the founding fathers of the United States to create a clause in its new Constitution to ensure that the money printing experiment would never happen again. Under Article I, Section 10, the states were not permitted to “coin Money; emit Bills of Credit; [or] make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts.”

Of course, this section in the Constitution has been totally ignored today as trillions of dollars have been created in the greatest money printing experiment in history. When money printing is the only tool of the government, it is the answer to every problem in the economy. The allure of the power to print currency is powerful and it corrupts almost every lawmaker.

As with every bout of currency printing in history and the currency collapse that followed, the money printing experiment we are witnessing will fail, and fail it will, spectacularly.

Today, the United States has 8,133 tons of official gold reserves with an estimated value of about $500 billion dollars. The official M1 money supply, the narrowest measure today, stands at $20 trillion – 4000% more than the nation’s gold reserves. However, unlike in the eighteenth century, the U.S. debt is much more complicated today if we take into account outstanding bonds and unfunded liabilities. A mountain of debt is pyramiding upon a comparatively small amount of gold.

Unlike mortal men, gold and silver have been around for over 5,000 years. They are inanimate, unable to defend themselves from the schemes to suppress or manipulate them. However, they are the personification of value given that every atom is gold and silver and this is the reason why humankind will always gravitate toward precious metals as an equitable medium of exchange. If gold and silver were alive, they will bid their time knowing that they will have their time in the sun again when humankind realizes that all the printed currency is not worth a Continental.