Why the Feasibility of a Sustained Fed Rate Hike is Doubtful

Despite the U.S Federal Reserve (Fed) disappointing market analysts by not increasing its benchmark interest rates at its September 2015 meeting, rate hike expectations are rife again as we go into the final week towards the last Fed meeting of the year on December 15.

Since December 2008, the Fed has kept interest rates at record lows of 0 to 25 basis points. It was a knee-jerk reaction to address the need for liquidity in the economy with the onset of the subprime mortgage crisis of 2008.

Since that crisis, the Fed has injected trillions (yes, put twelve zeroes behind it) into the economy through quantitative easing (QE) and has embarked on its Zero Interest Rate Policy (ZIRP) for a record 7 years.

Let us examine a few major economic indicators and follow the Fed’s line of reasoning to understand why the real economic situation should not lead the Fed to the conclusion of the need to increase interest rates.

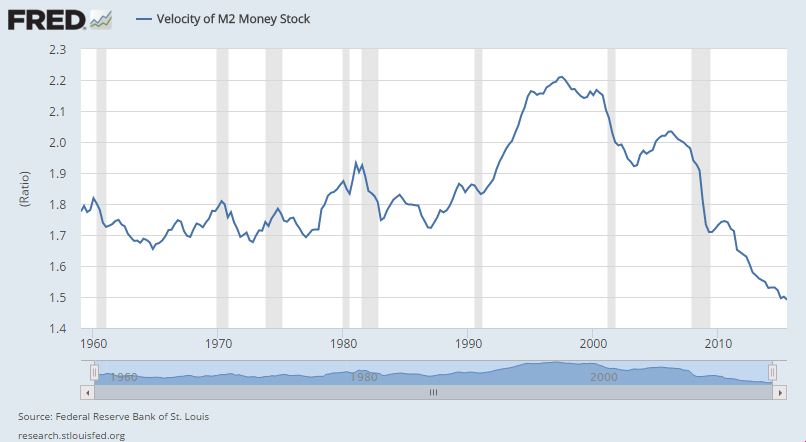

Why hike when money velocity is down?

Despite the U.S GDP growing nominally from USD 14 trillion to USD 17 trillion between 2008 and 2015, an important indicator that contributes to the calculation of the GDP is telling us a different story.

That indicator is money velocity which is measured as the number of times a dollar was spent in the economy during the past year. It is often used as a gauge of the economy’s strength or the willingness of people to spend money.

Unfortunately, the money velocity chart below is not showing a pretty picture of the present U.S economy. In fact, money velocity has now hit an all-new record low since the data was recorded since 1959.

It is evident that since the crisis of 2008, money velocity has only edged lower year after year.

Given that GDP is calculated by multiplying the money velocity with the money supply, the growth in the U.S GDP can be attributed to an increase in money supply since money velocity is dismally down.

This is consistent with the Fed’s relentless QE programs which expanded the U.S money supply(M2) from USD 6.9 trillion before the 2008 crisis to over USD 12 trillion today. Evidently, the growth in the U.S GDP is largely due to the Fed’s money printing ways.

Given that money velocity is at record lows, wouldn’t an increase of interest rates drain liquidity from an already weak economy and cause a further downward spiral of the money velocity?

Why hike when we are in the midst of deflation?

A falling money velocity is also deflationary in nature since money is hoarded and not spent within the economy. This is contrary to what the Fed intends to do. Since the crisis of 2008, the Fed has reiterated its intention to ignite inflation towards their acceptable 2 percent target.

It was for the purpose of achieving this target that the Fed held interest rates near zero for so many years. The low interest rate environment makes it easier for banks to extend loans using their reserves for a profit whilst offering an attractive low loan interest to businesses and consumers. This was a reason given by the Fed themselves for keeping interest rates low on the Federal Reserve website:

"Low interest rates help households and businesses finance new spending and help support the prices of many other assets, such as stocks and houses."

Increasing the interest rate on bank reserves held with the Fed may accomplish the opposite - increasing the incentive for banks to earn a risk-free interest by not lending out their reserves. This would contradict their intention for businesses and consumers to have easier access to credit to spur consumption and support asset prices.

Unfortunately, the official U.S rate of inflation has stubbornly hovered below 0.5% since the beginning of 2015. If the Fed's target inflation rate is persistently not reached due to deflationary pressures, slowing the pace of banks' lending will further add to deflationary pressures.

With the inflation rate still stubbornly stuck below the Fed’s target inflation rate, wouldn’t an interest rate hike cause further deflation going by the Fed’s logic?

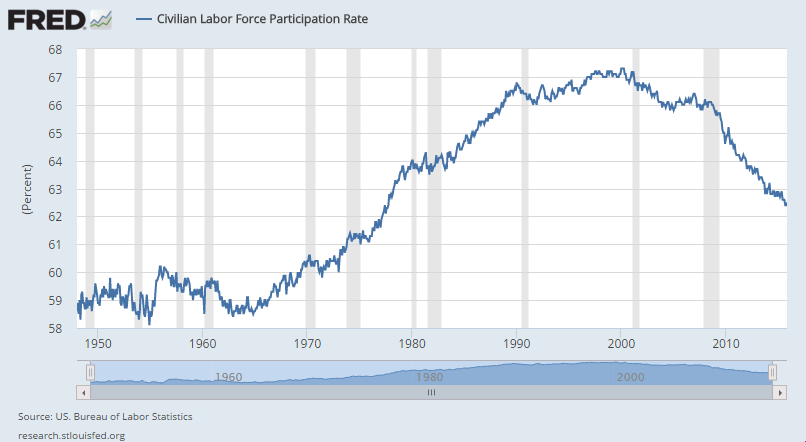

Why hike when real unemployment is high?

One of the reasons that the Fed has given for a possible hike in the interest rate was a significant improvement in the U.S labour market.

Putting contentions of how the U.S unemployment rate is calculated aside, the official unemployment rate has declined from a high of 10.8% in 2009 to the present 5%. This paints a rosy picture when the media reported solely based on the unemployment rate.

However, if we look at the labour participation rate, it tells a different story. The labour participation rate shows the size of the U.S workforce. It includes people who are working or actively looking for work. It excludes those who have left the workforce due to retirement, gone back to school or have given up looking for work entirely.

Like money velocity, the labour participation rate has continually fallen since 2008. It has reached levels last seen in 1977! As recent as September 2015, an estimated 95 million Americans were not in the labour force.

Fed Chairman, Janet Yellen, has also acknowledged that the unemployment rate understates the dwindling labour force in her September press conference:

"As I said, although we're close to many participants and the median estimate of the longer-run normal rate of unemployment… There are additional margins of slack, particularly relating to very high levels of part-time involuntary employment, and labour force participation that suggests that at least to some extent the standard unemployment rate understates the degree of slack in the labour market.”

Given that the big picture of the labour data is showing that unemployment is much higher than the official rate, how is it possible to say that the monthly jobs creation numbers warrant an interest rate hike?

Whichever way the damning evidence of the true dismal state of the U.S economy is seen, it is hard to fathom how the Fed could entertain the feasibility of a sustained hike in interest rates at this moment. It makes us wonder if those whom we have tasked to steer the global economy is thinking straight or are they starting to contradict themselves.